Introduction

The Sukhoi Su-75 “Checkmate,” first unveiled at the MAKS-2021 air show, has been positioned by the United Aircraft Corporation (UAC) as a cost-effective, fifth-generation light tactical fighter aimed primarily at the export market. Marketing materials have consistently touted its high operational range, payload capacity, and advanced avionics suite.

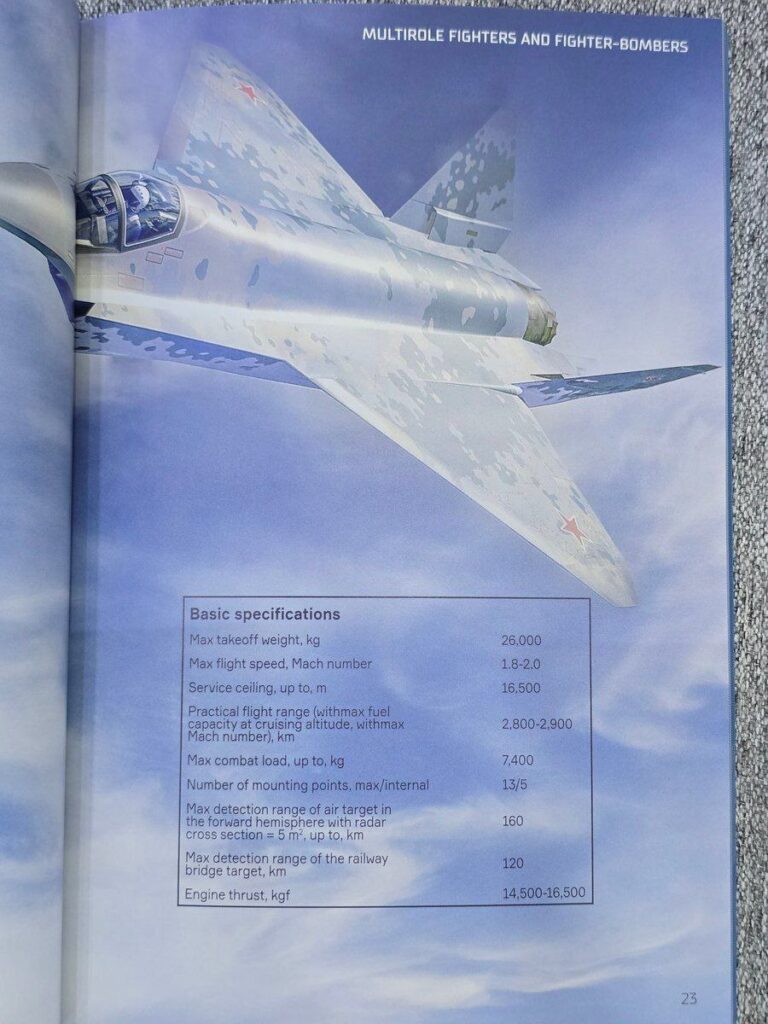

However, recent documentation surfacing within defense circles—specifically an image of a non-secret export catalog circulating on Iranian Telegram channels—has raised concerns regarding the actual capabilities of the aircraft’s onboard radar. If accurate, these specifications suggest performance metrics that lag significantly behind modern standards and, in some parameters, fail to surpass Cold War-era interceptors.

The Alleged Specifications

The data in question outlines the detection range of the Su-75’s onboard radar system. According to the leaked document, the radar possesses a detection range of 160 kilometers for a target with a Radar Cross-Section (RCS) of 5 square meters in the frontal hemisphere.

In the context of aerial warfare, a target with an RCS of 5 m2 generally represents a standard, non-stealth fourth-generation fighter jet (comparable to an F-16 or MiG-29 without reduced observability treatments).

Historical Benchmarking: A Regression in Capability?

To understand the skepticism surrounding these figures, it is necessary to benchmark the Su-75 against historical platforms. The alleged performance of this “promising” modern fighter appears comparable to, or arguably weaker than, heavy interceptors from the 1970s and 1980s.

- The F-14 Tomcat (USA, 1972): The Hughes AWG-9 radar utilized by the F-14 was capable of detecting a target with an RCS of 5 m2 (or slightly less) at ranges of approximately 213–215 km when operating in high pulse repetition frequency (HPRF) mode.

- The MiG-31 (USSR, 1981): The capabilities of the “Zaslon” passive electronically scanned array (PESA) radar are well-documented. Official data suggests a detection range of 160–180 km for similar sized targets (5m2), typically citing a detection probability (Pd) of 0.5.

While it must be acknowledged that the F-14 and MiG-31 were heavy interceptors capable of carrying massive radar apertures and power supplies, the Su-75 benefits from fifty years of technological advancement. The expectation for a modern Active Electronically Scanned Array (AESA) radar—even one housed in a smaller nose cone—is that signal processing and efficiency should yield superior results to vacuum-tube or early solid-state era technology.

Comparison with Contemporary Russian Platforms

The concern is amplified when comparing the Su-75 to current Russian frontline aviation. The Su-75 is intended to operate alongside the heavy Su-57 and complement the Su-35S.

- Su-35S (Irbis-E Radar): The Irbis-E is a powerful PESA radar. Sukhoi claims detection ranges significantly exceeding 160 km for standard fighter-sized targets, often citing ranges up to 350–400 km for larger targets in specific search modes.

- Su-57 (N036 Byelka): As a fifth-generation platform, the Su-57 utilizes a sophisticated AESA suite. While specific classified data varies, its detection capabilities for standard targets are widely accepted to be superior to the figures leaked for the Su-75.

Operational Implications for Future Combat

The primary critique of the 160 km detection range lies in the nature of the modern battlefield. The Su-75 is marketed as a fighter for the future, where it must engage not only legacy aircraft but also:

- Low-Observable (Stealth) Aircraft: Targets with an RCS of 0.1 m2 to 0.001 m2

- Cruise Missiles: Low-altitude, low-RCS threats.

- UAVs: Small composite drones.

If a radar struggles to detect a large, “bright” 5 m2 target beyond 160 km, its detection range against a stealth target (0.1 m2) would likely be reduced to distances that place the Su-75 well within the engagement envelope of enemy missiles, effectively nullifying its first-look, first-shot advantage.

Potential Technical Nuances

There are potential explanations for these modest figures that do not necessarily indicate a failure of engineering:

- Probability of Detection (Pd): Soviet and early Russian specifications often utilized a Pd of 0.5 (50% chance of detection). If the Su-75’s 160 km figure is based on a stricter Western standard (e.g., Pd of 0.9 or 90%), the actual performance would be significantly higher than the raw number suggests when normalized against older radar stats.

- Export Limitations: It is common practice for nations to downgrade the avionics of export variants (“monkey models”) to protect sensitive domestic technology. The catalog may reflect a degraded version of the radar intended for specific clients, rather than the domestic Russian Aerospace Forces version.

Conclusion

The leaked specifications regarding the Su-75 Checkmate’s radar performance present a paradox. For a fighter marketed as a cost-effective alternative to the F-35, possessing radar capabilities ostensibly inferior to 1970s interceptors is a significant marketing and operational liability.

Unless these figures represent a highly conservative estimate based on near-certain detection probabilities (Pd > 0.9), or are specific to a heavily downgraded export variant, they raise serious questions about the utility of the aircraft in a modern environment dominated by low-observable threats. It remains imperative for official sources from UAC or Rosoboronexport to clarify these specifications to alleviate concerns regarding the project’s viability.

Wow that was unusual. I just wrote an extremely long comment but after I clicked

submit my comment didn’t show up. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Regardless, just wanted to say

wonderful blog! https://tiktur.ru/

скажите спасибо большое за ваш интернет-сайт помогает много.

Посетите также мою страничку Мастерская обратных ссылок https://linksbuilder.fun/

Отличный интернет веб-сайт!

Это выглядит действительно хорошо!

Поддерживайте хорошо работу!

Посетите также мою страничку почтовые электронные аккаунты https://friendpaste.com/4LBZCrkJBfOLloJti3IJPb/edit

Вау, потому что это чрезвычайно отлично работа!

Поздравляю и так держать. Посетите также мою страничку получить обратные ссылки http://my-idea.net/cgi-bin/mn_forum.cgi?file=0&gcmes=2486157120&gcmlg=1185698

В основном хотел выразить я восхищен что я пришел на

вашем веб-странице! Посетите

также мою страничку поиск обратных ссылок на сайт https://yipee-yeah.com/more-on-making-a-dwelling-off-of-backlink-building/

Поддерживать невероятную

работу!! Люблю это! Посетите также

мою страничку отели на сутки https://wiki.manualegestionedocumentale.test.polimi.it/index.php?title=Utente:ArturoGillott5

Indexing and indicant checking overhaul for Google and Yandex.

Link Building Workshop

Who potty profit from this Robert William Service?

This table service is utilitarian for internet site owners

and SEO specialists WHO neediness to increase their visibleness in Google and Yandex,

meliorate their place rankings, and increment organic dealings.

SpeedyIndex helps apace index number backlinks, raw pages, and website updates.

Backlink Workshop https://hipolink.me/speedyindex

Appreciate the recommendation. Will try it out. https://truepharm.org/

Поддерживать полезно работу и вносить в толпу!

Посетите также мою страничку Квартиры на сутки http://gamgokbiz.co.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=free&wr_id=1180521

Ого, ты уже пробовал платить

криптой по QR-коду?

Криптовалюты сейчас штурмуют мир,

и это не просто слова! Забудь

про долгие переводы или возню с кошельками — сканируешь и

готово! А главное — это реально удобно, сейчас объясню.

Плати с выгодой: крипта по QR без комиссий

Серьёзно, первый раз оплатил такси криптой через QR,

и это было легко и быстро. Просто взял телефон,

навёл камеру на QR-код, и всё, сделка

в кармане! Это реально затягивает, держу пари, тебе зайдёт.

Как платить криптой по QR?

Чтобы оплатить что-то криптой по QR-коду, тебе нужен цифровой кошелёк с поддержкой QR.

Скачай, например, Coinbase Wallet, или любое приложение, где есть сканер QR-кодов.

В магазине или онлайн тебе показывают QR-код, ты его сканируешь, жмёшь «Оплатить»,

и готово! Всё о безопасности QR-платежей в криптовалюте

Самое крутое — это удобство.

Плюс, это безопасно: QR-код шифрует данные, так что твои эфиры в надёжных руках.

Попробовал оплатить подписку — и ни одной проблемы,

всё как надо!

Где это работает?

Крипта по QR-коду уже внедряется в магазины, кафе и даже онлайн-сервисы.

Например, в некоторых кафе в больших

городах уже принимают ETH через QR-коды.

Просто ищи значок крипты на кассе или спроси у продавца — они

обычно в курсе. Навёл — оплатил

Онлайн это ещё проще: многие интернет-магазины

добавляют оплату криптой через QR.

На сайте жмёшь «Оплатить

криптой», сканируешь QR, и дело

сделано! Попробовал оплатить игру через QR — и

это было легко и просто.

Зачем тебе платить криптой по QR?

Оплата криптой по QR-коду — это не только круто,

но и шаг в будущее. Забудь про лишние проверки — крипта и QR решают всё!

А ещё это не светит твои финансы, что всегда

плюс.

Честно, платить криптой через QR — это прям

будто в игре! Когда ты сканируешь код

и видишь, как эфир улетают за

покупку, чувствуешь себя человеком будущего.

Просто попробуй — это реально круто!

Платежи криптой? Используйте QR и забудьте о кошельках!

Пора платить криптой?

Серьёзно, QR и крипта — это удобство в твоём кармане!

Попробуй один раз, и, держу пари, ты не

захочешь возвращаться к старым способам.

Просто установи аппку, найди место, где

принимают крипту, и вперёд!

А ты уже пробовал платить криптой

по QR? Поделись своей историей!

Почему стоит платить криптой через QR-код https://nanscreativeadv.com/jenis-huruf-timbul-neon-box-yang-populer-di-semarang-jawa-tengah/

Why users still use to read news papers when in this technological world all

is available on net? https://meds24.sbs/

Indexing and power checking avail for Google and Yandex.

SpeedyIndex google

Who throne benefit from this servicing?

This service is utile for web site owners and SEO specialists

who want to gain their visibility in Google and Yandex,

better their site rankings, and step-up organic traffic.

SpeedyIndex helps promptly forefinger backlinks, young pages, and web

site updates. fast indexing tool free https://speedyndex.taplink.ws

Невероятно индивидуально дружелюбно веб-сайт.

Огромный информация доступный несколько кликов.

Посетите также мою страничку seo продвижение сайта в

поисковых системах https://forum.nsprus.ru/profile.php?id=21067

Эй, слышал про оплату криптой по QR-коду?

С криптой жизнь становится круче, согласен?

Забудь про долгие переводы или возню с кошельками — QR-код решает всё!

Это будущее платежей, и я расскажу,

как оно работает. которой можно пользоваться уже сейчас

Серьёзно, первый раз оплатил доставку криптой через QR, и это было легко и быстро.

Больше не нужно вбивать кучу данных.

Попробуй, и поймёшь, почему все об этом говорят!

Как это работает?

Секрет прост: нужен телефон с криптокошельком.

Скачай, например, Trust Wallet, или любое приложение,

где есть сканер QR-кодов.

На кассе или в интернет-магазине

тебе дают QR-код, ты его сканируешь, подтверждаешь сумму, и всё — деньги отправлены!

Почему стоит платить криптой через QR-код

Самое крутое — это простота.

И главное — безопасно: QR-коды шифруют

данные. Я как-то оплатил новые кроссы через QR, и всё прошло быстрее, чем наличкой!

Где можно платить криптой по QR?

Платить криптой через QR можно уже почти везде.

Видел, как в сервисах всё чаще

берут крипту по QR? Ищи логотипы криптовалют или спроси на

кассе — продавцы обычно знают.

Будь на шаг впереди: плати криптой через QR

В интернете вообще сказка: многие

магазины уже поддерживают QR-оплату криптой.

Заходишь на сайт, выбираешь

«Оплатить криптовалютой», сканируешь QR-код, и вуаля!

Попробовал оплатить VPN через QR — и это было легко и просто.

Зачем тебе платить криптой

по QR?

Оплата криптой по QR-коду — это не только удобно,

но и шаг в будущее. Забудь про банковские комиссии — крипта и QR решают всё!

А ещё это не светит твои финансы, что всегда плюс.

Честно, платить криптой через QR — это прям кайф!

Сканируешь QR, подтверждаешь, и бац — ты уже в тренде!

Просто попробуй — это реально круто!

Что нужно знать об оплате криптой

по QR-коду

Ну что, в деле?

Серьёзно, QR и крипта — это скорость в твоём кармане!

Попробуй один раз, и, держу пари,

ты не захочешь возвращаться к старым способам.

Бери телефон, сканируй QR — и делись

впечатлениями!

А ты уже пробовал платить криптой по QR?

Какой у тебя опыт?

Криптовалюта + QR = Удобная оплата без лишних движений https://excelpractic.ru/bitrix/redirect.php?goto=https://leonidkayum.ru/product/zakryityiy-razdel/

the Fugu site is an web-based casino that sits alongside a sports wagering hub

and a poker section in a unified site. In the casino catalog, players generally

get a large slot selection plus casino table staples

such as blackjack, the wheel game roulette, and baccarat options, with select titles

offered in live dealer versions. The experience is built for browsers,

so it generally plays on computers and phones through a responsive website.

Before playing, it’s smart to review closely the rules, especially around promo offers and turnover conditions, plus how different games are credited

toward those requirements. It also helps to understand withdrawal methods,

any min-max rules, and account verification that can affect cash-out speed.

Availability and licensing status can vary by region, so it’s worth confirming what’s allowed

where you are and using self-imposed limits.

Feel free to surf to my web-site; skydance

Izcila vietne šķiet kā tiešsaistes galamērķis, ko tu apmeklē un tūlīt pamanu, ka par lietotāju ir padomāts: viss ielādējas ātri, izkārtojums

ir tīrs, un tas, kas tev vajadzīgs atrodama pāris klikšķos.

Izvēlne ir saprotama, norādes ir vienkārši,

un jebkurā ierīcē — no telefona līdz lielam ekrānam — viss darbojas stabili.

Īstais iemesls, kāpēc tā ir “lieliska” nav tikai vizuālais — tas ir cik daudz

liekās berzes tā noņem. Meklēšana strādā kā vajag, formas netraucē, un galvenās

pogas nav apraktas. Tu aizej ar vienu skaidru secinājumu:

tā palīdz rīkoties ātrāk, darbojas tā, kā tu gaidi, un aicina atgriezties.

My web-site latvija

The Bovada sportsbook is an online

sports betting platform that offers sports wagering together with casino games and

poker. It covers a large variety of matches and tournaments, with common bet types such as moneylines, handicaps, over/under totals,

parlays, futures, and prop markets, plus live (in-play) betting as games unfold.

The platform is often aimed at recreational bettors and is recognized

for a simple interface and broad market coverage for big North

American leagues as well as international events.

Where it’s allowed and how it’s regulated depend on your location. Bovada is often described as

an offshore betting operator and may be unavailable in certain jurisdictions,

especially within the United States. Because rules and enforcement

can change, anyone considering using it should verify current

access and legal requirements for their specific region and ensure

they follow local laws and age restrictions.

Bovada’s sportsbookhttps://bovada.one is an internet-based

betting site that features sports wagering together with casino play and poker.

It lists a wide range of matches and tournaments, with popular wagers

such as straight moneyline bets, point spreads, O/U, combo parlays, season futures,

and props, plus live (in-play) betting during games. The platform is often geared toward casual bettors

and is often described as having a simple interface and solid market depth for top U.S.

and Canadian leagues as well as worldwide sports.

Where it’s allowed and how it’s regulated depend on the user’s

jurisdiction. Bovada One is

often described as an offshore betting operator and may be restricted in certain jurisdictions, particularly within the United States.

Because laws and availability may vary over

time, anyone considering using it should confirm access and legal requirements for their

specific region and ensure they follow regional

rules and age limits.